A Brief History of Handwriting: From Roman Capitals to Modern Cursive

Reading historical documents requires more than just sharp eyes. It often requires learning how to recognize and interpret writing styles that have changed significantly over time. This post offers a broad overview of western paleography and handwriting from the post-Roman Empire to the mid-20th century, covering writing styles in Europe and the Americas written in Romance and Germanic languages using Latin script.

Terms and Concepts

Before diving into styles, here are some terms that will help you make sense of what you're seeing:

Paleography: The study of historical handwriting styles, including how to decipher, date, and contextualize them.

Orthography: The standardized system of writing conventions for a language, including spelling and punctuation.

Majuscule and minuscule: Terms for uppercase (majuscule) and lowercase (minuscule) letters.

Ascenders/descenders: Parts of a letter that extend above the middle line or below the baseline, such as in "h" and "g."

Ligature: The joining of two or more letters into a single glyph, common in handwriting and early print.

Roman Capitals

Roman capitals were majuscule letters commonly seen carved into stone on monuments, and they continue to influence architectural lettering today. Some early Roman inscriptions used small dots to separate words instead of spaces. The word "roman" also refers to the typeface style that draws on this tradition.

Uncial and Insular Scripts (400–800)

Uncial script is rounded and entirely majuscule, used widely in Greek and Latin manuscripts. The "insular" variant refers to scripts developed in the British Isles. Because of their broad use, you’ll find many local variations.

Book of Kells

Carolingian Minuscule (ca. 773–1200)

Developed in France under Charlemagne, this minuscule script was easier to read than uncial and helped standardize communication across regions. It is the basis for both blackletter and humanist minuscule.

Carolingian Gospel Book

Blackletter (ca. 1150–1500s and beyond)

Blackletter emerged in the 12th century and was used across Europe well into the 19th century in some regions. Associated with German texts but found elsewhere, it was more compact and quicker to write than Carolingian script. Variants include Textura, Fraktur, Bastarda, and Rotunda.

Blackletter sample.

Humanist Minuscule (1400s)

Developed during the Renaissance in Italy, this script is more legible and less ornate than blackletter. It became the basis for many modern typefaces.

Humanist Minuscule Comparison

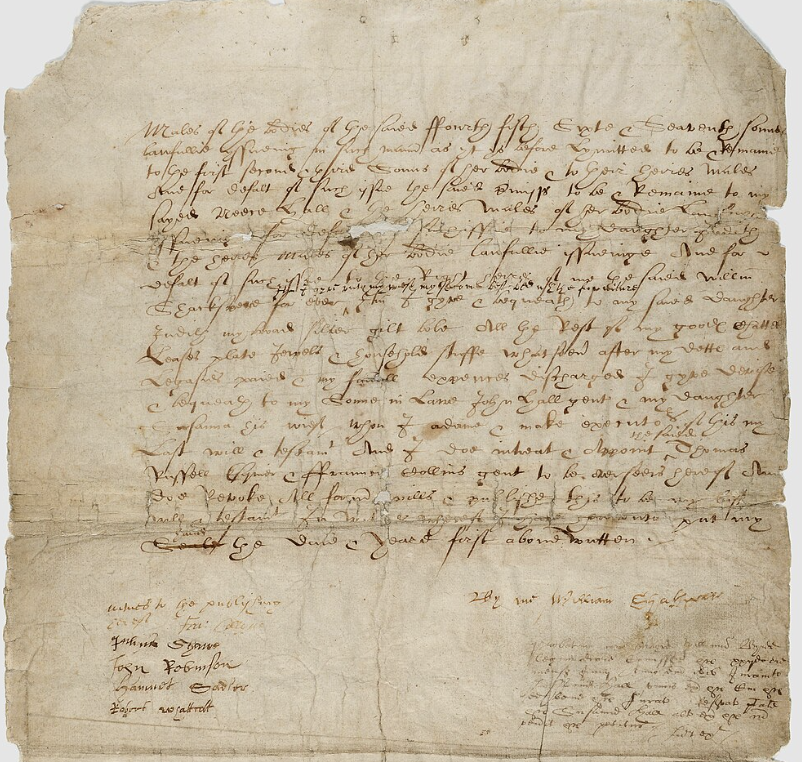

Secretary Hand (1500s–1600s)

This style was used for English, German, Welsh, and Gaelic documents. Easier to read than medieval scripts, it was widely used for official documents.

William Shakespeare's will, written in secretary hand.

Court Hand

Used in English legal documents, court hand was extremely compact and flourished. It became so difficult to read that it was eventually banned by an act of Parliament in 1731.

Court Hand Alphabet.

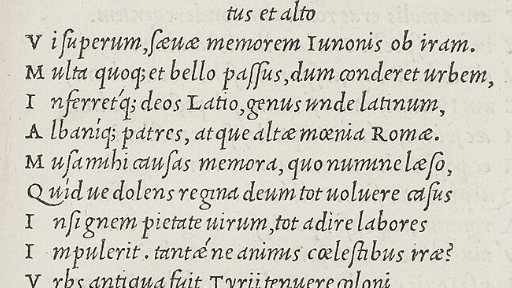

Italic / Cancellaresca Corsiva

Derived from Carolingian minuscule, this script was designed for quick, stylish writing. The pen is held at a 45-degree angle. Italic was used for both everyday and decorative writing.

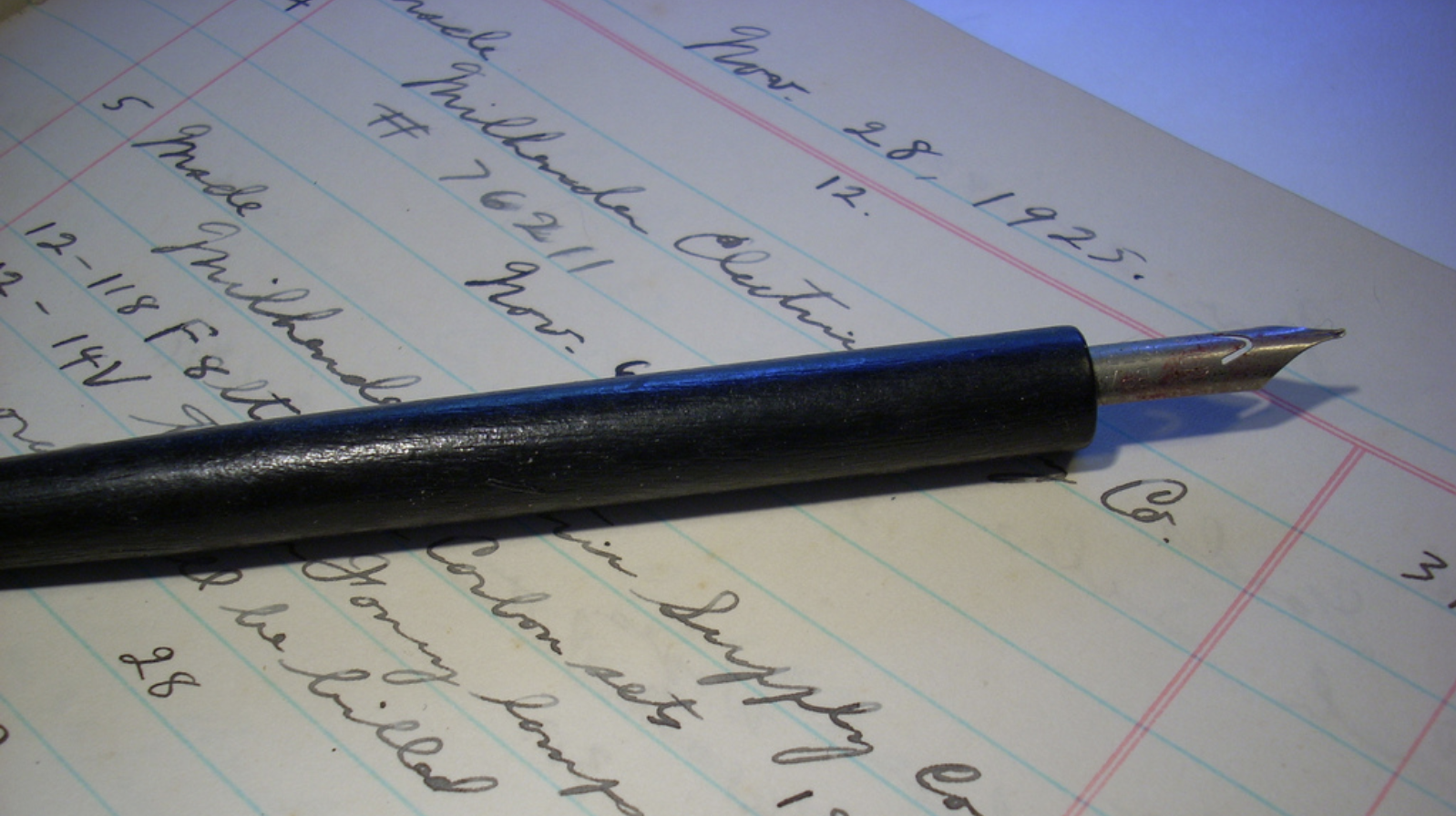

Writing Tools Over Time

Most scripts before the modern era were written using dip pens—quills or metal nibs dipped into ink. These required frequent re-inking but allowed for dynamic line variation. Fountain pens, developed in the Victorian period, introduced an internal ink reservoir. Ballpoint pens, with their uniform tip shape, lack the thick and thin lines produced by nibs.

Dip pen.

Modern Cursive Styles

Cursive handwriting allowed writers to keep their pens on the page more consistently, speeding up writing. Loops and ligatures became common. Many cursive styles emerged over the 18th to 20th centuries, especially in the business and education sectors.

Roundhand (1660s+)

Contrast of thick and thin strokes made possible by metal nibs.

Spencerian (1850–1920)

The standard in the U.S. for decades, this elegant style was based on copperplate script.

Spencerian Example

Palmer Method (1890s+)

Simplified from Spencerian to allow faster writing, popular in business.

Zaner-Bloser (1900s)

Created shortly after Palmer, it gained popularity in U.S. schools.

Zaner-Bloser Method.

D'Nealian (1965–1978)

A hybrid of cursive and print handwriting meant to ease the transition between the two.

Challenges in Reading Historic Handwriting

Nonstandard spelling: Spelling was often phonetic and inconsistent.

Long s vs. round s: The "long s" resembles an "f" and was used in earlier texts.

Cross-writing: Writers turned the page 90 degrees and wrote across the original lines to save paper.

Strategies for Deciphering Handwriting

Trace or replicate difficult scripts (try two pencils to simulate a nib).

Look for repeated letter shapes.

Read aloud and rely on context clues.

Identify verbs first to orient sentence structure.

Watch for terms like "instant," "ultimo," and "proximo" to determine timing.

Looking Ahead: Future Challenges in Handwriting

Thermal paper: Fades quickly and is hard to preserve.

Ink corrosion: Deterioration of old materials.

Less standardized handwriting: Especially post-20th century.

Evolving shorthand and the rise of emoji: Symbols, icons, and shorthand now play a greater role in communication.

Whether you're a researcher deciphering 18th-century letters or a genealogist exploring your family's documents, being familiar with handwriting styles can open doors to understanding the past. This overview just scratches the surface. Dive into resources like the Society of American Archivists or Lettering Daily to explore more about paleography and the history of handwriting.